Some people, unaware of what was accomplished during Muslim civilisation, believe that astronomy died with the Greeks, and was brought to life again by Nicolas Copernicus, the 15th-century Polish astronomer who is famous for introducing the sun-centred theory of the solar system, which marked the beginning of modern astronomy—even though it was not universally accepted.

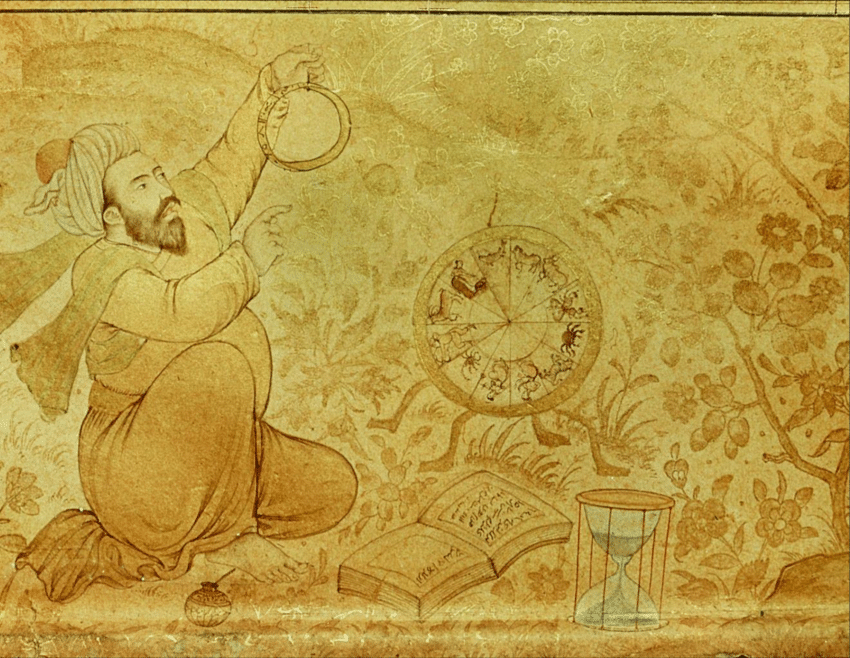

“An early seventeenth-century margin drawing from the folio in Jahāngīr’s Album showing an astrologer surrounded by his equipment—an astrolabe, zodiac tables and an hourglass (Werner Forman Archive/Naprestek Museum, Prague). ”

However, many historians now think it is not a coincidence that his geometrical models for the Sun, Moon, and five naked-eye planets are identical to those prepared by Ibn al-Shatir more than a century before him.

It is known that Copernicus relied heavily on the comprehensive astronomical treatise by Al-Battani, which included star catalogues and planetary tables. The mathematical devices discovered by scholars in Muslim civilisation before Copernicus referred to in modern terms as linkages of constant length vectors rotating at constant angular velocities are exactly the same as those used by Copernicus.

The only important difference between the two was that the former’s Earth was fixed in space, whereas the latter’s had it orbiting around the Sun. Copernicus also used instruments that were particular to astronomy in the East, like the parallactic ruler, which had previously only been used in Samarkand and Maragha observatories.* This instrument has been described by Ptolemy in his Almagest.

A 15th-century Persian manuscript of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi’s observatory at Maragha depicts astronomers at work teaching astronomy, including how to use an astrolabe. The instrument hangs on the observatory’s wall.

Comments

Post a Comment